A Simple Case for Studying Morals

Morals are hard. Studying them improve things for everyone, collectively and individually.

Morals is a complicated topic. So complicated that explanations for why it matters are themselves complicated. I have found that as a result, many have become alienated from morals, where they cannot seem to care enough to study them.

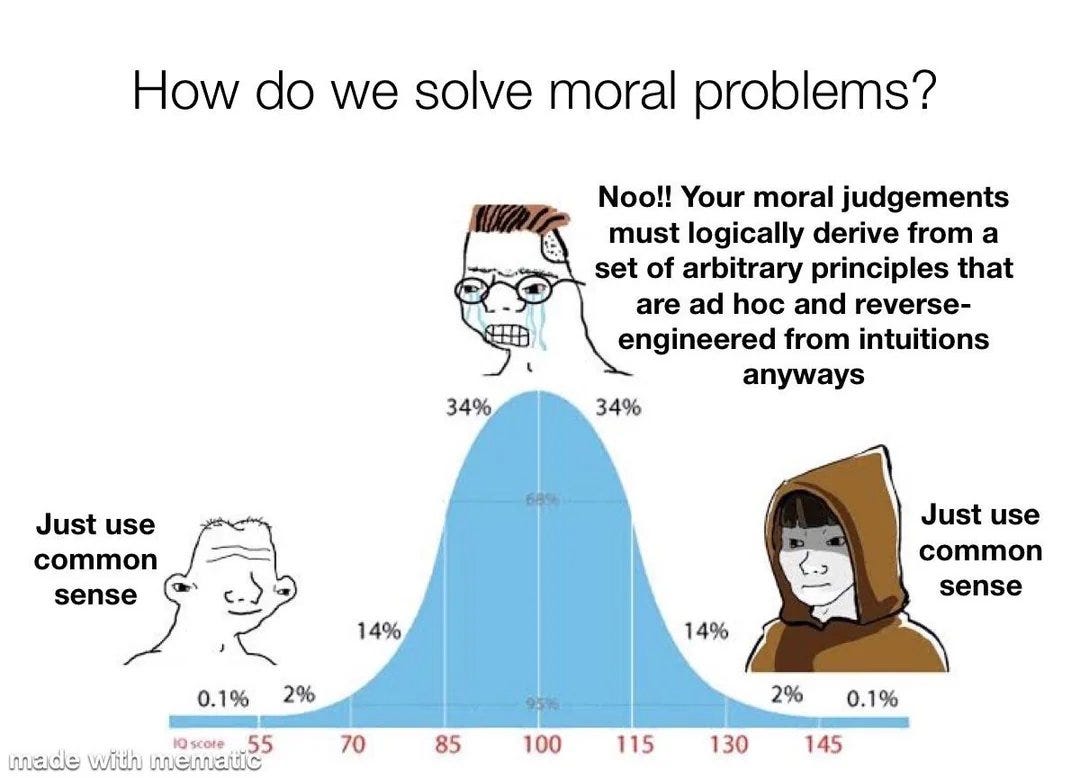

This leads to memes like this one:

Obviously, the meme is wrong. It's a meme, it doesn't purport to make precise and true claims. But it does point at a dynamic. This dynamic is that many people feel like the alternative to using common sense is to logically derive moral judgement from arbitrary principles.

This is very sad! Many have been so disconnected from morals that they see any type of moral inquiry as playing arbitrary word games.

In this article, I'll try to make a simple case for why we should study morals. I'll try to make it in as concrete terms as possible, without any theoretical considerations and philosophical jargon.

The Track Record of Studying Morals

More than any complex argument, I believe the easiest way to consider why it is worth studying morals is its track record.

The Past of Humanity

We performed many moral aberrations in the past. We now understand them to be bad.

This understanding is not purely psychological; it has real-world consequences. When what we identify as moral aberrations visibly happens, we publicly condemn them. When we have enough resources, we try to stop them from happening.

In the past, there were people who described moral aberrations in a way that was not the norm at their time, but was prescient of our current understanding. Those people usually studied morals.

Bartolomé de las Casas is an interesting example. Here is how Wikipedia describes his work and latter recognition:

Arriving as one of the first Spanish settlers in the Americas, Las Casas initially participated in the colonial economy built on forced Indigenous labor, but eventually felt compelled to oppose the abuses committed by European colonists against the Indigenous population.

[…]

Las Casas spent 50 years of his life actively fighting slavery and the colonial abuse of Indigenous peoples, especially by trying to convince the Spanish court to adopt a more humane policy of colonization.

Following his death in 1566, Las Casas was widely venerated as a holy figure, resulting in the opening of his cause for canonization in the Catholic Church.

The following anecdote makes it clear that his moral thinking led him to be in advance of his peers. It shows that even within his life time, he reasoned himself into better morals.

He then advocated, before Charles V, on behalf of rights for the natives. In his early writings, he advocated the use of African slaves to replace Indigenous labor. He did so without knowing that the Portuguese were carrying out "brutal and unjust wars in the name of spreading the faith". Later in life, he retracted this position, as he regarded both forms of slavery as equally wrong.

Conversely, there were people who described not moral aberrations, but moral virtues in a way that was not the norm at their time. These people usually studied morals too.

I believe the most famous emblematic of this is Socrates, the OG philosopher. He embodied many modern virtues, such as radical honesty and an early form of Cartesian Scepticism. He stood for his principles even in the face of overwhelming power, and got sentenced to death for it.

In the same vein, it makes sense to mention Giordano Bruno who was arguably tried to death for heresy because of his cosmological views (among others).

—

In other words, historically, students of morals both pushed against bad behaviours and pulled us toward better behaviours.

The Future of Humanity

I believe that even without understanding morals, we can look at the direction of moral progress, and make a few guesses as to how morals will develop based on it.

It doesn't mean that these guesses are morally good. Until we build an actual methodology that lets us understand and ascertain goodness, we are just poking at things. And guessing based on history is even more uncertain than other methods we use when we study morals.

For instance, it seems likely that in the future…

Our moral circle will expand, and we will come to see factory farming as a moral catastrophe.

Our economic wealth will increase, and we will come to see wage slavery as a horror on par with serfdom and slavery.

Our technological development will progress, and we will come to see our lack of direct effort toward eradicating ageing as reckless.

Many people who study morals have already warned about all of the above.

Individuals

Humanity has benefitted from people studying morals. Most of our moral progress comes from people who have spent time studying morals in the past. Many of them fell into extremist versions of their own morals, but overall, over time, we have collectively managed to take the good out of many contradictory moral systems and integrated into what now seems like obvious moral common sense to most people.

This might seem enough to make the case that we should study morals.

But I want to further my case, with the claim that it is also individually good for people to study morals. I contend that studying morals is not meaningful only in that it helps with the improvement of humanity, but also in that it improves the lives of the people who study said morals and the people around them.

First, a caveat. There are a few situations where studying morals can be wasteful or bad.

The wasteful ones are usually a type of nexus: a largely unproductive endeavour that captures an unjustifiable amount of time and energy.

Becoming an academic philosophy researcher who does not touch grass and interact with the world. Reaching a spiritual enlightenment that leads one to doing nothing but meditating and separating oneself from society. Or spending all one's time trying to internalise lengthy detailed static moral codes that do not reflect the changing nature of real-life.

But some are just bad.

For instance, at an individual level, morally ultra-scrupulous people spend too much time considering their actions. They often end up in anxiety loops which might lead to panic attacks.

More catastrophically, at a larger scale, groups that focus too much on morals often conclude that everyone (else) is bad, which sometimes leads to purity spirals, moral panics or purges.

Too much of anything can be bad. Barring exceptional cases like the above, studying morals is usually good for people.

When I talk about "studying morals", I mean regular things.

Writing down our actions for an hour every week and checking how much we disavow or endorse them after the fact.

Reading a bit on morals, whether it is from philosophy books, online blogs or religious texts, thinking about whether we agree with the principles present in these writings, and reflecting on the alignment between our actions and these principles.

It is easy to fall into habits and stop thinking about the morals of our actions. Then, we do things that end up being bad for us and others, not out of malice, but just out of ignorance.

—

I have personally, many times, heard a variant of "I regret having ignored some moral teachings".

But aside from extreme situations where people fall into some cult or ideology, I don't think I can recall ever hearing "I regret having spent time reading, reflecting or practising some moral teaching".

My favourite phrase that captures this dynamic is Socrates' "The unexamined life is not worth living."

There is a feeling that comes from fully endorsing one's choices, after reflecting about them, their consequences and the principles that bring us to make them. In this situation, even when our choices turn out badly, we do not regret them.

I am not sure what to call this feeling. Resolve? Clarity? Affirmation? Nevertheless, after having experienced it, it's hard to find unexamined choices meaningful. They just lack… substance.

The True Worth of Morals

So far, I have been quite superficial. I have only mentioned examples of morals being worth it. But to me, "Historically, something has been useful" is more of a sanity check than a reason to change my mind.

From my point of view, the reasons for why we ought to study morals are painfully clear. It is simply that it deals with many problems that we can't naturally answer by ourselves.

Morals is a very large topic. It deals with values, principles, norms, how to live one's life, how to live together, and much more.

But here, I'll focus on a more restrictive aspect of morals. An aspect that deals with one of the most important problems that one must answer as a human; and that we ought to collectively care about, as humanity.

Namely, What are our values?

What are our values?

It's all too easy to miss what matters. Very few of us are gifted with perfect clarity, gnosis and science over our own mind.

It's all too easy to forget. We might notice something special about ourselves, that we felt special some day or after some event. But then, we forget. We don't write it down, we fail to act upon the feeling in the moment, and caught in the stream of our busy lives, we forget.

It's all too easy to fail to consider it at all times. Even if we have moments of clarity, even if we do not forget, our intuition is just not that great. Sometimes, it just fails to integrate important considerations into important decisions, and we only remember them days after we made the relevant choices.

And there are many different things that we value.

We value feelings. We love feeling happiness, awe, pleasure, connection, flow, meaningfulness, love, accomplishment, confidence, and so much more. Unless we learn and consider all of them, it's too easy to live a life that misses a core emotion that we care about.

We value the world being a good place. We want to have no natural catastrophes, thriving ecosystems and for our world to be welcoming to us humans.

We value humanity being well. We want everyone to be free from scarcity, disease, suffering and be able to pursue their happiness.

We value embodying virtues. We want to be brave, curious, wise, kind, disciplined, humble, reasonable, and dependable.

We value doing the right thing. We want to abide by core principles, such as respecting each other, protecting each other, telling each other the truth, and at the very least, not harming each other.

We value beauty. We want to reach the sublime. It's not only that we care about feeling awe. A chip or a chemical that triggers the feeling would make it meaningless. What we want is for there to exist things that are awe-worthy, intrinsically beautiful and wonderful.

We value relationships. We want to have built and to build long-lasting relationships with people. We want to form memories, and share experiences. We want to love.

I can go on for a while. We care about our history, about our legacy, about personal and collective growth, about spiritual and sacred matters, and much more.

—

But I want to talk about a special one.

We value other people's values.

There are many values that I do not care for personally. Yet my partner, my friends and my family do. And that's enough for me to care about them.

But this does not stop here. My close ones care about their close ones' values, which makes me care about them too. And this goes on and on.

And I also care about my parents and my grandparents' values. Even though all of them but one are dead, their values still matter. They also cared for their parents' values. And this goes on and on.

And we care for our children's values. We hope to give them a great world.

There is this beautiful chain of how we all care more or less about everyone's values. A chain that extends from the past to a hopefully long and prosperous future.

How does studying morals help?

I believe that it is easy to miss a whole section of the spectrum of values. I believe that I could not have easily come up with all of this by myself, and that I would have certainly missed a lot of it.

To understand all these values that I and people care about, I had to spend time studying morals.

This study involved hundreds (thousands?) of hours-long conversations asking people what they deeply cared about, in many different ways.

When I was younger, I would talk to tens of people every day online. Compared to real-life, it took much less for people to confide in me, and I could just talk to many more people.

I spent so many hours talking to many people in parallel, asking them about everything in their lives. I learnt a lot, and people felt great about sharing with me. Win-win.

This informed my understanding of values quite a bit. (As well as many other things. People are very traumatised and it seems that both child and domestic abuse are extremely common.)

People just value many different things, and build their entire lives around many different facets of the human experience. Many of them that I truly did not care about, and at first, I had trouble understanding them as anything but "Are they stupid caring about things that do not matter and make no sense?" as opposed to "They care about different things, and they care in different ways".

Without this, I expect that I would strongly miss an internalised sense of how varied people's values are.

My study also involved reading philosophy books presenting many different strands of moral philosophy, texts from philosophers, articles from Wikipedia and the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, blog posts, and more.

This is closer to what people think of when they think of studying morals.

But I think this is usually an extremely reductive view. Instead, I tend to think that it is useful, as part of a wider study. But their place is often misunderstood.

I believe that any serious inquiry into any part of reality, including its more moral aspects, starts with looking at reality. In the case of values, it's the type of things I mentioned before. Learning about oneself by trying many things and introspecting. Learning about others by learning about their lives, talking to many people and reading testimonies.

Then, out of this, one may start to build their own theories and analyses. In this context, reading philosophy is great. It is a wealth of theories, investigations, analyses and meditations from people. They are not a substitute for my own thinking, but they're a great source of inspiration for when I don't know where to look, when I'm stuck or just reading about many different approaches to check that I'm not missing anything crucial.

I tend to believe that the main obstacle to any serious inquiry is not learning, but unlearning. I wrote more about it here.

This is even more true as part of studying values!

My study involved a lot of introspection and reflection.

At some point, I had to acknowledge that I did not have a perfect understanding of what I valued. I had to unlearn my expectation that I would always be right about myself: it is actually quite common to be wrong about what we want. It then became obvious that I had a much worse understanding of what others valued.

After going through successive rounds of unlearnings, it became much easier to notice things that I dismissed in the past. Once the hard part was done, I could then much more easily think about those topics with clarity.

In my study, I had to avoid traps laid down by ideologues. Moral ideologues only acknowledge values that fit their paradigm and do not contradict their assumptions.

There are so many of them. Communists, libertarians, utilitarians, religious extremists, and more.

I think the easiest way to avoid those trappings is to study more. Talk to more people, read from more varied sources, reflect more, and assume some amount of good faith and intelligence in all those places.

I find that noticing key information becomes much easier when I assume that:

Everyone, everything, every text, every feeling, is wrong.

Nevertheless, they point at some shard of the Truth.

With this frame of mind, it's harder to get trolled and captured by some specific idea. And it's much easier to not be uselessly cynical. Before discarding anything, I ought to at least understand what it's grasping at.

Theoretically, there is a slight possibility that I could have ended up where I was or a better place without studying morals.

But I doubt it. I expect that like most people, I would have mostly been carried away by the currents of life.

Life rarely gives us the time to stop and ponder, alongside all the relevant information on a nice platter.

This is why we must take the time and the attention to study.

More Methods

I have only mentioned three tools in my toolkit.

There are many more ways to study morals. Debates, logic, experiments, meditation, etc.

—

Similarly, What are our values? is but one of the many core questions of morals.

There are many more.

We all have different and contradictory values, how do we reconcile them?

As individuals, we have many values, but not enough resources to satisfy them all, how do we juggle between them?

Sometimes, it's not clear what we value, and it seems more like a choice. How do we decide our values? How should we decide our values?

Introspection is hard. What can we do to make it easier? Would it be possible to design a long checklist of experiences that we go through to see if we resonate with many different values, kind-of like a blood test?

Our intuition is often wrong. What are principles and heuristics we should keep in mind to act in accordance with our values?

Some decisions are critical and we have time to ponder them, like deciding who to marry or the new economic policy of a country. Can we design processes for these decisions that are much better than what we would have done otherwise?

I contend that none of these questions are obvious, settled, and that we can do much better than what we are doing at all of them.

I contend that we would all be better for doing so.

I contend that we can do so by studying morals.

Conclusion

Studying morals is good. It's good for humanity as a whole, and good for individuals.

Sadly, it's not clear what it would look like to productively study morals. Academic philosophy is obviously not it, but there is no clear contender.

I will likely write in the future about my opinions on how we can each practise and study morals, as well as how we could create a meaningful science of morals.

On this, cheers everyone!

== The world (including our own brain and body) is complex, morality is not. ==

morality only seems hard because people try to load, "literally anything that can happen as a consequence of your actions to anyone that might hurt them or infringe on their basic human rights", under "morals". this is kinda silly.

----------------------------------

== Slavery. ==

slavery is a bad example for "we used to be immoral because morality is really complicated", because, -- most of all because "no fucking way people thought slavery was okay" --

but also, it's just really convenient to have slaves and do slave trade, and there was more incentive for it, and less cultural and legal things pushing back on it.

the abolishment of slavery was a political/legal/social-cooporation victory, not a moral or philosophical one. (rhetoric that shows clearly why slavery is bad, that was just ammo for that battle, doesn't count as "philosophical progress")

----------------------------------

== People know things are bad. ==

for factory farming: everyone knows it hurts animals, it's just annoying and depressing to act on it or worry too much about it.

for tribal violence/mindset: i strongly doubt that anyone in human history, who was not evil/sadistic or literally retarded, actually thought that the suffering of other tribes was irrelevant or that in some alternate version of the world with much more abundance and comfort, those "outsiders" still deserved to suffer -- it was just not the right thing to care about.

(similar with giving to charity)

----------------------------------

== The meme is correct. ==

"just dont do stuff that makes people feel bad".

figuring out the consequences of actions and finding the right attitudes or frameworks, that's not "morality", that's "having to solve really complicated problems".

----------------------------------

(i dont wanna polish this further because it's kinda obvious to me, and, you never respond anyway)

(except for adding some things for clearer reading because, holy crap the comment display on this website is so bad)