Human Fine-Tuning

What do you call the thing that includes all of learning, operant conditioning and trauma?

We constantly change, as time passes and we experience the world.

We learn and we forget.

We get addicted and traumatised.

We build habits and lose them.

We discover new facets of reality, and start ignoring them.

Our personality changes. We change.

The question of how people change is complex. But it is critical for understanding the world, how it shapes us, and how we shape ourselves.

This question is among the most important ones in psychology. It underpins memory, trauma, our sense of self-worth, our relations to others, AI psychosis, and so much more.

—

Paradoxically, despite how pervasive it is, there is no name for this phenomenon.

For the change we go through as a result of experiencing something.

There are more specific words, like “conditioning” or “learning”.

There are more generic ones, like “change” and “transformation”.

But there is none for the actual thing. So I will arbitrarily pick one: Human Fine-Tuning”.

Before analysing Human Fine-Tuning in depth, let’s start with a few examples.

A Few Examples

Vocabulary List

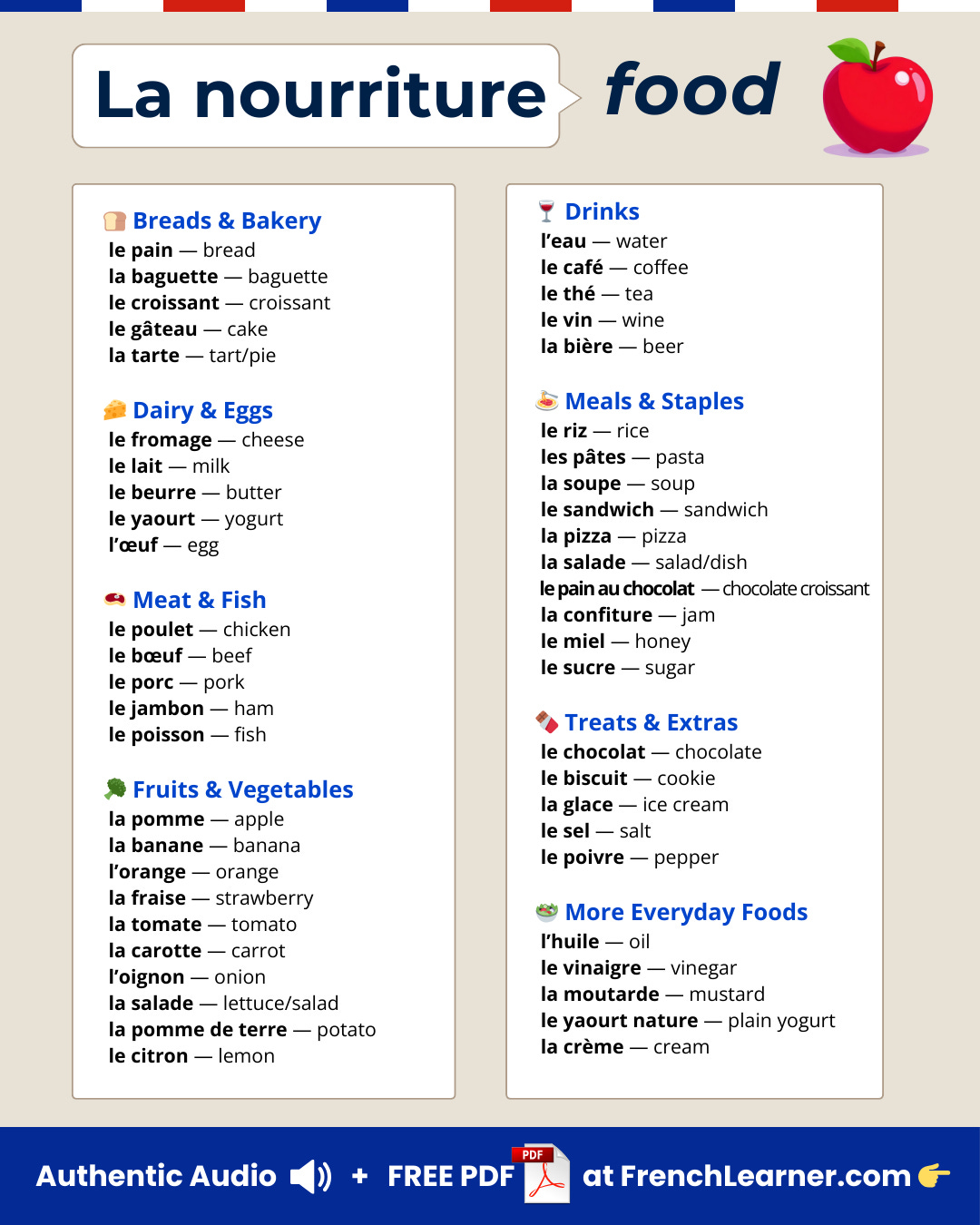

Sometimes, the changes to our brains are directed and purposeful. In which case we call it learning.

For instance, we set out to learn a vocabulary list in a language in which we hope to become fluent. By doing so, we hope to enact many changes on our brains.

First, we want to learn to understand that new language. More precisely, we want our brain to naturally conjure the relevant concepts when faced with the words.

Second, we want to learn to speak fluently in this language. When we need to express the concepts from the list, we want the words to come naturally. However, this is hard to get just from working on a vocabulary list. So, at the very least…

Third, we want to keep the list of words in our memory. That way, when we will need to express the relevant concepts, we will be able to think hard about them (instead of having the words come naturally), recall the relevant words, and construct our sentences with a bit of effort.

All of this, knowing that the more we practice, the more fluent we’ll get.

But the changes do not stop there.

Fourth, we develop familiarity with the language.

We get a feeling of its etymology: does the language mostly come from Greek, Latin, Chinese or Arabic?

We get a feeling of how it sounds, and what it looks like. Does it have an alphabet, or ideograms? Does it have a simple set of sounds, or a large variety of throat consonants?

We get vibes of how the words are constructed. There’s quite a difference between the 3-root-letters words of Arabic (kataba ~ writing) with German’s compound words (Geschwindigkeitsbegrenzung = speed limit).

Even with something as direct and directed as a dumb vocabulary list learnt by heart, there’s a lot to say.

American Diner

However, most changes to our brain are not purposeful and directed.

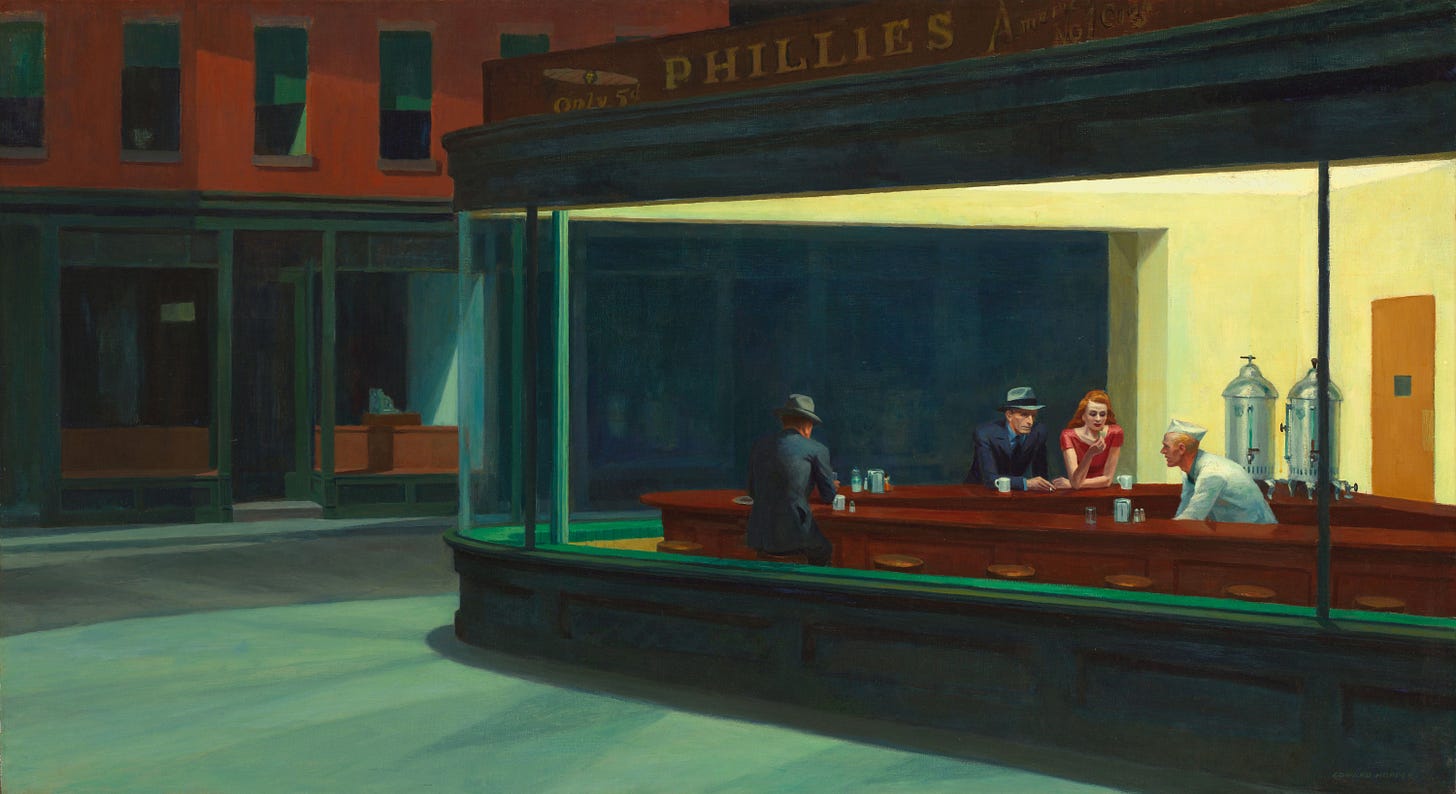

As I was writing this, I remembered a fun anecdote.

When I was younger, I had seen many American diners in movies – or TV Shows, it’s hard to remember and that’s kind-of the point.

I never thought much about these diners. I’d see them, largely ignore them, and focus on the plot instead.

I hadn’t even learnt the word “diner”. As a Frenchman, and because of their ever-present context, I simply assumed it referred to a special type of restaurant (which it did!), never paying much attention to it.

But nevertheless, in the background, a lot happened.

Even though I never paid the word “diner” much attention, I had a feeling the US would be filled with these recognisable restaurants: pancakes, coffee, nice waitresses, cozy booths with their red-vinyl benches, a counter with its typical wooden stools.

Coincidentally, 10 years ago, a friend invited me to a French “diner”. Or let’s say, a pale imitation of one. It was much too clean! The red vinyl was not cracked: it was shiny. It didn’t feel cozy at all, it was artificial, the music was slightly too loud, and the neon lights were a bit too kitsch.

I didn’t think much of it back then. But reflecting on it, it is actually quite impressive.

I had built an opinionated aesthetic sense of a thing that I had never experienced myself. That I had never even named.

Just from seeing them from time to time in movies, I came to associate them with certain attributes, certain feelings. And visiting the one in France; it felt dissonant. Or more than dissonant, it felt wrong.

I don’t think there was a big conspiracy, where Big Diner was trying to sell me more Diner, where diner chains lobbied all of Hollywood to systematically feature them in movies and show specific qualities.

It just happened. The aesthetics of a French kid fed on Hollywood movies was moulded in a meaningless way. That’s just the way the world and our brains work.

But it happens to everyone, constantly. Simply by exposing ourselves to pieces of art and media, we build strong opinions about everything. Said opinions inform our experience of the world and thus our actions, without us noticing that we even formed them.

Loss

So far, I have been pointing at minor changes. But sometimes, these changes can be big.

Like most people who have the chance to live long enough and build meaningful relationships, I experienced loss a few times.

My latest loss experience hit close to home, was particularly violent, and had a sizeable blast radius.

Loss hurts everyone, both in similar and different ways.

But what personally hurt me was having to witness people close to me lose a part of themselves. Each of them had been durably changed, and for the worse.

A visible hole had been carved in their soul. I can see the sadness through their eyes whenever a topic directly reminds them of the loss. They visibly carry more weight: they stand less straight, they are more tired, and they are less optimistic.

It is tragic. Violent loss is of one of these few experiences that make people into a durably worse version of themselves.

Why am I writing about this? Not to make you sad. I promise there is an actual point.

—

The point is that young enough, I had noticed that adults looked like they were missing a bunch of obvious things.

They had lived their entire lives without learning a facet of engineering and building things, without ever pursuing an art form and creating, without trying to get into politics.

When discussing and debating, they would miss obvious arguments, and would get angry when I’d try to correct them.

They were missing so much. Experiences, lines of reasonings, courses of actions; which all seemed obviously important to me. It felt like adults were dumb, for no good reason, and in a way that resisted me trying to help them.

Over time, I figured out what was happening. It’s not that they were dumb and missing the obvious things. It’s that they were explicitly avoiding them. These things made them feel bad.

They knew their artistic pursuit would be a struggle, they knew they were likely to fail any ambitious political endeavour, and they wanted to avoid that.

Later, I learnt about the word trauma in the context of PTSD.

Even later, I learnt its more generalised meaning of emotional damage.

This made it easier to communicate the observation from above.

People get traumatised. As a result, they become behaviourally stupider versions of themselves, in a way that resists mending.

From my point of view, people accumulate chip damage over time. And ultimately, they die of a thousand cuts. They are too damaged to willingly try new things and put themselves out there.

This has been one of the sadder parts of my life. Seeing people slowly lose Their Spark as they internalise all the bad things that happen around them.

Mechanical Analysis

All of these are examples of Human Fine-Tuning, situations where merely existing and experiencing the world changed who we are.

These situations are all different. Some are happenstance, and others are purposefully directed. Some are purely logical word-level associations, and others are deep changes to who we are.

More often than not though, we naturally mould ourselves into what we perceive.

This general process of “a brain changing” doesn’t really have a name. So I am going to apply to people the closest term that I know: Human Fine-Tuning (HFT).1

Fine-tuning involves applying additional training (e.g., on new data) to the parameters of a neural network that have been pre-trained.

Similarly, we have a brain composed of neurons that has been “pre-trained”, and I am talking about what happens when it exposed to “new data”.

Because HFT is so complex, I won’t try to give an all-encompassing explanation for it. Instead, I’ll go through 4 different high-level mechanisms.

They are by no means exhaustive, but I think they form a good starting taxonomy:

Associations. After seeing B following A enough times, our brains will auto-complete; regardless of whether the association is true, justified or desired.

Aesthetics. Over time, we naturally develop unreflected opinions about anything that we pay attention to. We often mistake them for endorsed judgments.

The Audience. We imagine the reaction of people whose approval we seek. Experience changes which people these are, and how we imagine them.

Ontological Nudges. Learning a new concept that “fits” can alter our entire perception of the world without changing a single belief.

1) Association

Associations are the simplest mechanism. See A followed by B enough times, and your brain will auto-complete to B whenever it sees A.

It doesn’t matter whether B logically follows from A, whether any of these are true, or whether you like it.

The quintessential version of this is Deez Nuts. Whenever a friend ends a sentence on the word “these”, say “Nuts”. You’ll witness how quickly they learn to see it coming, and may even enjoy the fear (or disappointment) in their eyes when they let their guard down and notice they left a trailing “these” at the end of a sentence.

French is filled with these.2 “Quoi? Feur.” “C’est qui qui a fait ça ? C’est kiki !” “Hein ? Deux.”

—

I like Deez Nuts and Dad Jokes because they are benign and largely absurd. No one is deceived by them.

Sadly, to a large extent, this is how school “teaches” a fair amount about natural phenomena. “Why is the Sky Blue?” → “Scattering”.

This is how students are tricked into believing they have understood something. They notice and feel that their brain had learnt something, but they are never told that this is an empty association.

Idiocracy makes fun of this phenomenon. In the movie, people are watering crops with a sports drink (Brawndo). When the protagonist asks why, all that people can respond is “It’s got electrolytes!”, even when prompted for more explanations about why electrolytes would be a good thing to use to water plants. “Why is Brawndo good?” → “It’s got electrolytes!”

Ironically, real-life makes fun of Idiocracy. Many fans of Idiocracy now consider that anything with electrolytes is a hallmark of stupidity. Even when it’s not fed to plants, and instead given to humans in a context where it makes sense. They have learnt the association “It’s got electrolytes” → “It’s stupid!”, and do not realise that it is empty. This is how we end up with such threads.

—

Back to Deez Nuts. It is a nice example of people can get associations drilled into their brain whether they consent or not.

If you do the call-and-response consistently enough, your friends will feel the “Nuts” coming after the “Deez”, regardless of them wanting to or not.

Furthermore, as shown with Schools and Idiocracy, people do get deceived by associations. They don’t naturally notice how empty they are.

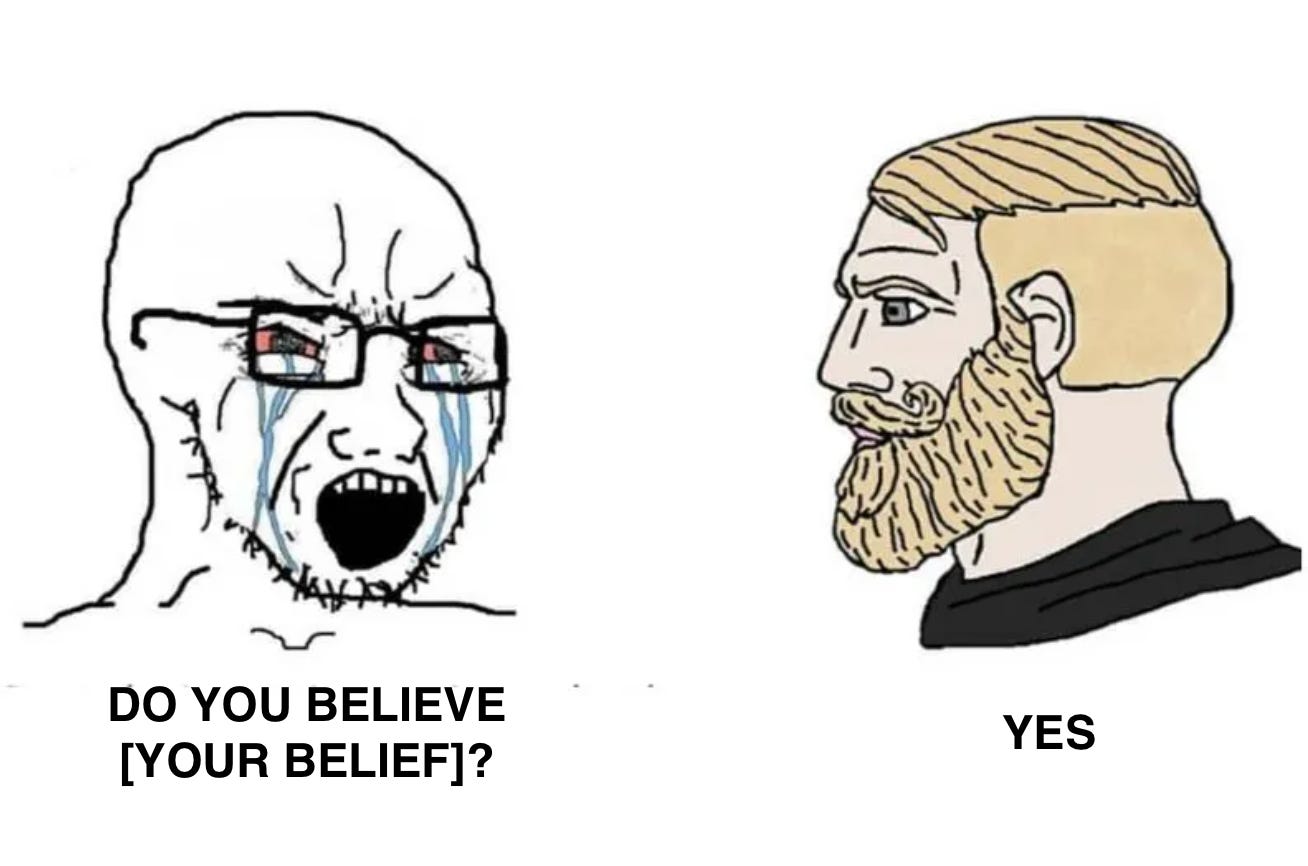

One may wonder. Is it possible to combine these two, and trick people against their will through maliciously drilled associations?

The answer is “Of course. And people do so constantly.” Much of rhetorics, memes and art is built precisely on this.

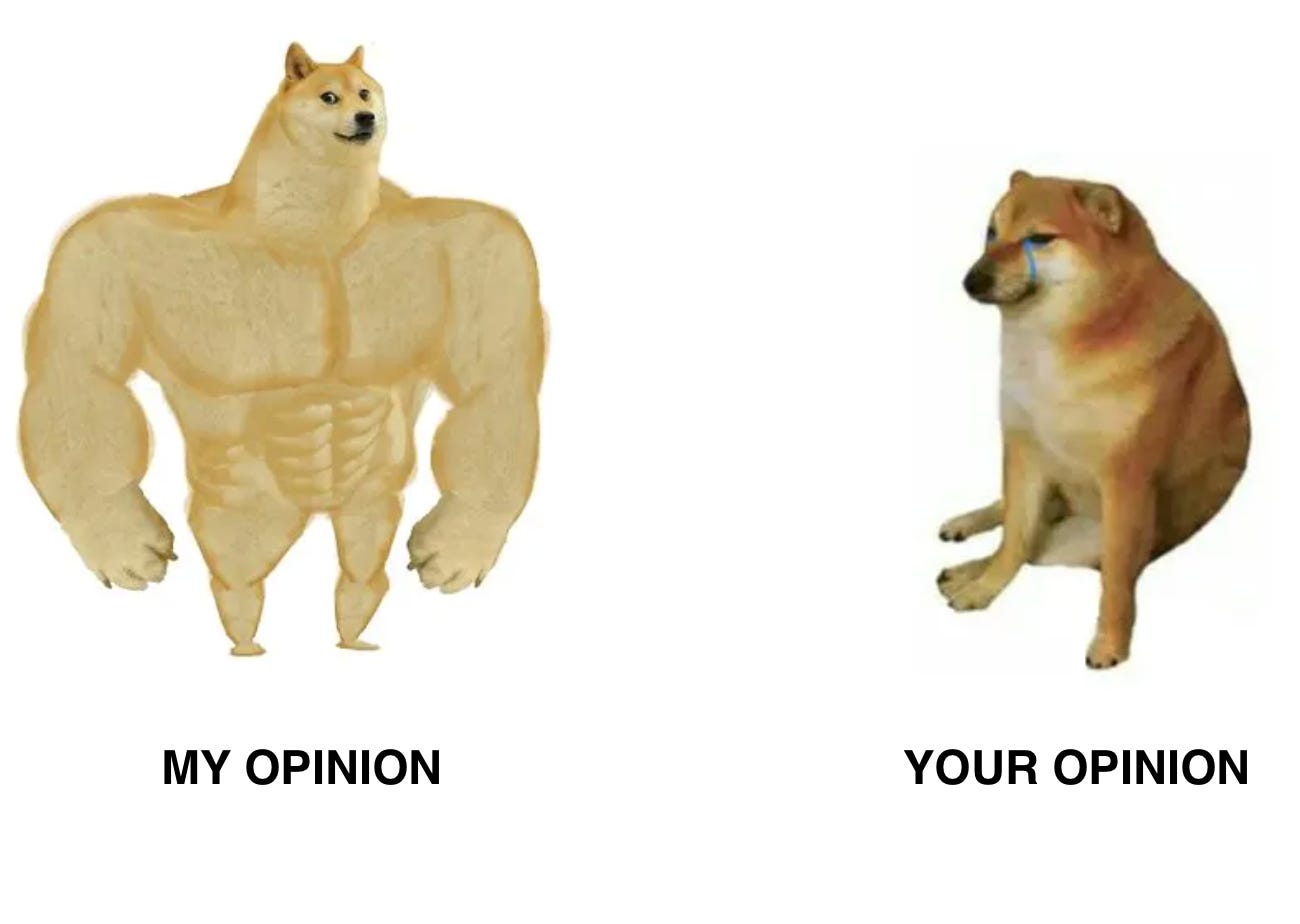

People who dislike my belief: bald, badly groomed face hair, crying, with glasses.

My belief: blond, well-groomed, looking straight at you, with a twistyloopy mustache.

My opinion: Standing, buffed, dogecoin.

Your opinion: Sitting, crying, sad doge.

—

In real-life, the memes are rarely that straightforward.

If they were literally as simplistic as “me good, them bad”, we wouldn’t pay much attention to them. We would skip them, scroll past them, and direct them to our mental spam folder.

So instead, they feature a level of indirection. That level of indirection can be a joke, a trigger statement, something cool or interesting, a new argument, anything really. Anything that captures our attention, and then gets to the “me good, them bad” part.

That is all that is needed for the fine-tuning to happen. Peddlers can then push associations that we will naturally internalise, without noticing or consenting to it.

—

Associations are straightforward and very salient. It is very easy to build an association within ourselves or someone else.

But not all HFT is about inferring and completing patterns.

2) Aesthetics

Aesthetics are more subtle than associations.

“Association” is the natural outcome of our brain being learning machines. Brains love learning.

“Aesthetics” is the natural outcome of our brain being value machines. Brains love judging.

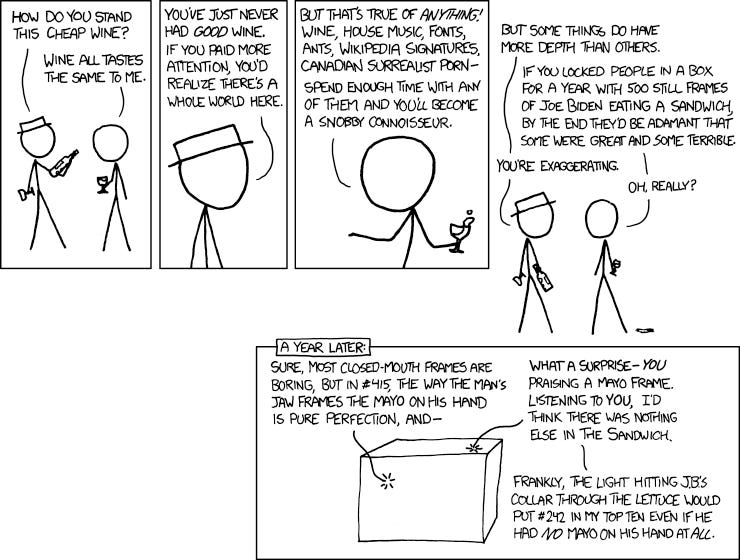

This XKCD comic explains it in a funny way.

Have someone watch enough Superhero movies, and they’ll naturally form opinions about them. They may feel strongly about them. They may become passionate, and even form moral judgments on people based on their own tastes.

Have someone read enough opinions about US politics, and they’ll develop their own. Even if they’re not from the US.

This effect is pernicious. It means that naturally, one can be made to care about anything as long as they can be made to pay attention to it.

And this can get worse over time. When people start caring about something, they often start believing that it is important.

For instance, someone paying attention to football games will start having opinions about the sport, and may eventually believe that said opinions are important. Same thing for Reality TV, video games, nerd lore, etc.

—

But the brain-hack doesn’t stop there.

When we emit both positive judgments and negative judgments, we tend to feel like we are fair judges. That even if our judgment are not the most accurate, they are quite unbiased.

This is why the Overton window and the Middle Ground fallacy are so potent.

Let’s say that someone is only ever exposed to rightist opinions. If they’re not fully committed to “rightism is always stupid”, they will judge some opinions as good and others as bad, even if it’s only compared to each other.

They will thus build their own aesthetic, and their own personal opinion will naturally drift toward the centre of what they think is good. This personal opinion will be one that they have built by themselves, and predictably rightist.

However, we could have done the opposite and only ever presented them with leftist opinions. In that case, their own personal opinion would have been a leftist one!

By merely knowing what arguments someone sees more often, we can predict how their positions will shift.

—

This also explains the Fundamental Attribution Error.

People tend to think of themselves as – if not perfect – fair reasoners.

Let’s say we have Alice, Bob and Charlie. Alice is conflict avoidant, Bob is normal, and Charlie is aggressive.

From each of their points of view, their own level of conflict is fair.

Alice doesn’t literally always say YES to people. If she did, she’d be a proper slave, fulfilling everyone’s desires.

Of course, she has her own criteria for when to say yes or no. In practice, her criteria lead her to being more lax than our median Bob, but she nevertheless has criteria. Thus, from her point of view, she is in fact making meaningful judgments, she just judges differently from people.

Conversely, Charlie doesn’t literally always say NO to people. If he did, he’d be a fully anti-social person and end up in jail.

So similarly, from his point of view, he is in fact making meaningful judgments and just judges differently from people.

Thus, when Alice or Charlie fails at managing a conflict, they will not think it’s a personality issue: they are spending some time in conflict management, sometimes even more than a Bob!

Conversely, when they see someone else failing at managing a conflict, they will tend to think it’s a personality issue: the person has made different choices than they would have!

—

Aesthetics percolate all aspects of the human experience.

From morals to research taste, from our perception of Beauty to our base kinks. Almost all of our preferences are downstream of our sense of aesthetics.

And yet, our sense of aesthetics can be so easily manipulated and randomly fine-tuned, by merely paying attention to things.

Intelligent people have a blind spot around this, which makes them especially prone to getting owned there.

Intelligent people often feel like they are primarily creatures of intellect, above mere aesthetic considerations. Because of this, Aesthetics lies their Shadow. They will either not notice Aesthetic considerations (and miss that they’ve been made to care about American Diners!). Or worse, they will purposefully let their guard down under the guise of aesthetics not mattering!

—

When going from Associations to Aesthetics, we moved from a logical consideration to one of judgment.

Associations can be thought about in objective terms. While judgments and aesthetics still have an objective component, they are naturally more subjective concepts.

This made it harder to write about. But the next topic goes even deeper.

3) The Audience

The Audience is a deeply psychoanalytical concept. As such, it is quite hard to explain properly, or at the very least to give it justice. I’ll try nevertheless.

—

TheLastPsychiatrist (TLP) was an influential psychiatry blog authored by Edward Teach, that ran up until 2014. In it, he often discussed TV shows and movies. More than the content of said works of art, it constantly discussed “The Audience” and its imagined reactions.

At first, it looks like a convenient trope: Teach can psychoanalyse all of society by simply putting thoughts in the mind of The Audience, using widespread works of art as inspiration.

The first level of analysis is simple. Narrative works of art fine-tune The Audience. And TLP describes the process of fine-tuning, as well as its results.

—

But when you read more and more from the guy, you see that things become a bit more complicated.

Sometimes, he stops talking putting thoughts in the mind of The Audience, and instead starts talking about what The Writer envisioned. He tries to answer the question “Why did The Writer write things that way?” to explain why stories are so convoluted.

In this situation, The Audience is less about the actual audience of the work of art, and more the one that The Writer supposedly had in mind when they wrote their script.

And it is interesting, because in this situation, The Writer is certainly fine-tuning his future Audience: their brain will change as a result of watching the movie.

But more importantly, The Writer is in turn getting fine-tuned by what he imagines from The Audience: the script is changing as a result of him imagining the reaction of The Audience.

—

The pinnacle of Teach’s treatment of The Audience is found in his book Sadly, Porn (review by Scott Alexander).3

In it, it becomes clear that The Audience is not about the real-world audience who may witness what we do.

The Audience lives within our minds.

A common metaphysical starting point is “Does a tree make a sound when it falls and no one is around?” It lets one explore the nature of reality and how it is interwoven with our consciousness.

Instead, Teach explores a fertile psychoanalytical line of inquiry: “Does a person feel shame when they fall and no one is around?”

The answer is Yes!

Teach’s answer is The Audience.

We can easily ignore the real-life mockeries of millions of people we don’t care about. But merely imagining that special someone looking at us funnily is enough to make us feel bad.

This is what The Audience is about. This is who it is. Not the special someone, or at least, not the one from the real world. It is the imagined special someone that resides in our mind.

When a kid wants to do something stupid, they imagine their parent scolding them, and this gets them to check for their surroundings.

This is The Audience.

The Jesus in “What Would Jesus Do?”, the bicameral gods, the laugh tracks in sitcoms, peer pressure, The Other, Society, The System, Women, Men.

—

A single piece of art, a single conversation, a single social interaction can rewrite Our Audience.

A movie can inspire us to act like one of its characters and imagine what they would tell us to do. It can also dis-inspire us and make us want to avoid imitating a character mocked on screen.

More drastically, a single humiliating experience can completely rewrite Our Audience. Being Rejected in front of People.

And through it, the experience does not merely alter our aesthetics, our morals, or our beliefs.

It does much, much worse.

It rewrites our social emotions.

Our entire understanding of the social world.

What’s Cool and what’s Cringe.

What’s Pride Worthy and what’s Shameful.

What’s Confidence Boosting and what’s Humiliating.

Who is Authoritative and who is Conspiratorial.

What argument is Elegant and which is Convoluted.

Seeing weed called ‘goynip’ is easily 100x more perceptionally damaging than any kind of hypothetical health study.

—

In the end, I think my treatment of The Audience was not that bad. But I’ll quit the psychoanalysis.

Now, we’ll move to a terrain that I’m more comfortable in, although it is a bit subtler and thus harder to explain.

It has little to do with our associations, judgments or social senses.

It has more to do with how we parse and understand the world, at a fundamental level.

4) Ontological Nudge

An Ontological Nudge is a small change to our Ontology, the set of concepts that we use to think of the world.

Let’s start with a short example.

When I was a young child, I learnt about “nests”. As in, regular bird nests. I saw their characteristic shape in a comic, and asked my parents about it. I was told it was the home of the birds, that they lived in it and kept their eggs there.

It made a strong impression on me. And when I saw one in a tree in the city, I was excited! I learnt about a new element and recognised it in the world.

I grabbed my parents, and pointed at the nest. Then, I was disappointed. No birds came out of the nest. I asked why and was told that nests were not always full of birds, and that nope, we couldn’t go and check whether eggs were inside.

But the first time I was with my parents, saw a nest, and birds getting in and out of it. It was crazy. Boy was I excited.

My Ontology was expanded, and it felt great.

—

In the example above, what’s happening is hard to describe.

Basically, a new concept had been introduced into my brain. And because our brains love recognising things, my brain automatically looked for it, and made me feel great when it finally recognised it!

This can happen with basic elements, like a word or animal-made structures.

Most importantly though, the same happens with more advanced concepts.

Like the Woke “micro-aggressions”.

The Nerd “incentives”.

The Freudian “projections”.

The Consequentialist “utility functions”.

Learning about such general concepts is very pernicious. While they don’t change our beliefs, they change our ontology. The very building blocks that we use to interpret the world.

And they can be changed so innocently. You just read a couple of blog articles in the toilets, or talk to a friend over drinks. You see or hear a word you don’t know about. You check it out online or ask your friend.

Boom, you start recognising it everywhere.

After that, all of your subsequent observations are tainted forever.

—

It doesn’t matter whether “incentives” or “micro-aggressions” exist or not.

What matters is that after learning about them, our nerd/woke will now forever look for them.

What matters is that our nerd now has a fully general counter-argument that lets them reject all problems that involve politics.

“It’s the incentives!”

Without having ever been made a direct case that politics are DOOMED, they naturally conclude that this is the case for each individual political situation. It’s the natural outcome of a nerd having learnt about “incentives”.

They would have rejected a direct case that politics are DOOMED. They are reasonable.

But by changing their ontology, there is nothing to be rejected. Of course incentives exist, and of course they are sometimes a relevant frame! How could you reject that?

Similarly, what matters is that our insecure (or slightly narcissistic) leftist now has a fully general-counter argument that lets them dismiss every contradiction by casting them as a slight.

“It’s a micro-aggression!”

Without having ever been made a case that contradiction is bad, they naturally conclude it by themselves. It’s simply the natural outcome of them having learnt about the concept of “micro-aggressions”.

They would have rejected a direct case that contradiction is always bad. They are reasonable.

But by changing their ontology, there is nothing to be rejected. Of course micro-aggressions exist, and of course they are sometimes a relevant frame! How could you reject that.

—

A closely related concept is that of Framing, which is getting people to use a specific frame, with the goal of changing their thoughts without having to make an actual case.

Ontological Nudges are deeper than a simple frame. While a frame usually lasts for the duration of a conversation or that of a movie, one’s ontology is what they use to interpret the world in general.

Ontological Nudges are also usually smaller than a full frame. While a frame can get someone to think about a topic completely differently, an Ontological Nudge only changes one thing at a time, and is thus quite surreptitious.

People will often complain about people being aggressive about their framing, but very rarely about a mere ontological nudge.

Conclusion

I believe that HFT is a pervasive phenomenon that affects everyone.

It affects you, it affects me, and it affects everyone else.

Internalising how it works is crucial for understanding the world. Furthermore, everyone likes to think they are above that. But no one is.

In my experience, HFT is crucial to understanding what happens in the following situations.

People get converted and de-converted.

Public intellectuals get captured by their audience.

Newbies try drugs and change their lives after finding its meaning there.

Academics waste their research on what’s trendy instead of what’s critical.

Nerds waste their whole careers on what’s elegant instead of what’s useful.

Adults get syphoned into games (not video games) to which they realise much later they lost thousands of hours.

Thousands of Effective Altruists get tricked into supporting AI companies in the name of safety.

Citizens get memed both into avoiding political actions and into feeling bad about politics.

LLM power-users fall prey to AI Psychosis.

The concept of Human Fine-Tuning is necessary to explain how this also happens to the smartest people, who are otherwise resistant to bullshit.

It is at the core of cognitive security and defensive epistemology. I’ll deal with these more meaty topics. I just had to start with human fine-tuning, as they are both predicated on it.

On this, cheers!

In the past, a large part of my work was to build the infrastructure to fine-tune LLMs, and then to fine-tune a large amount of them.

These…

Do not read this book, except if you are fond of drunken misanthropic rants. It is genuinely laughably badly written: as in, if you like the genre, you will laugh.

Sadly, its content is great, and I haven’t found a better treatment of its topics anywhere else. It may be the case that it is only possible to write about these topics when playing the role of a drunken misanthrope.

Thank you, very interesting, looking forward to see how you build further topics on this. Also, "death by a thousand cuts" felt very close to my experience.. Would be cool if you share some day what you personally do to avoid that. Is that possible at all, or is it our inevitable end?

The section on ontological nudges reminds me of "man with a hammer syndrome": https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/WHP3tKPXppBF2S8e8/man-with-a-hammer-syndrome